Culbin, Findhorn

Culbin Golf Club. Instituted 1926. A 9-hole course, at Findhorn.

Scotsman July 7th, 1926

“A new nine-hole course was yesterday opened at Findhorn, the last of the Moray Firth resorts to come into line and provide golf for its visitors. Situated amidst a wide expanse of rolling bents, forming ideal golfing ground. Findhorn until recent years was principally a fishing village, but the decline of the fishing industry has forced the community to concentrate on developing the place as a summer resort. The course, which is 3000 yards in length, is situated on the opposite side of the Findhorn estuary from the Culbin Sands, the famous waste of sea-sand which covers what was once one of the most fertile estates in the north. The opening ceremony was performed by Major Munro Ferguson of Novar, brother of Lord Novar. Major Munro Ferguson drove off the first ball, and an exhibition game was afterwards played between George E. Smith, Moray, the ex-Scottish professional champion, and Alexander Phimister, the Grantown professional, who laid out the new course.”

Our grateful thanks to both Bill Shand and The Findhorn heritage society for below.

“A sporting little seaside course in natural surroundings, within a few minutes walk of a beautiful sandy beach (for bathing). The course is at present under reconstruction, but it is hoped it will be ready for play in Summer 1947. 2,341 yards, Par 36, SSS 34.” (SGC Mar 1947).

This latter statement was, in fact, quite wrong. The course was taken over by the army in 1940, and turned into a camp and training ground. The damage was so considerable that after the war the erstwhile golfers could not afford the large sums required to restore the course to a usable state.

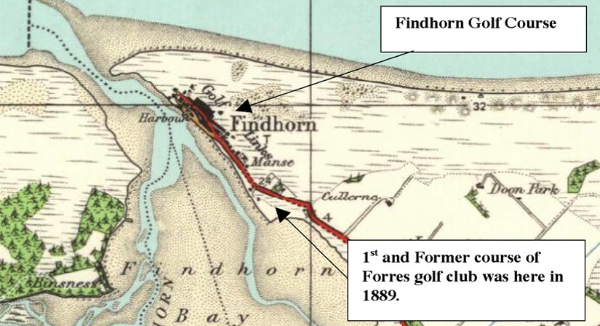

Findhorn Golf Course

July 6th 1926

REQUIEM FOR A GOLF COURSE by William (Bill) Shand

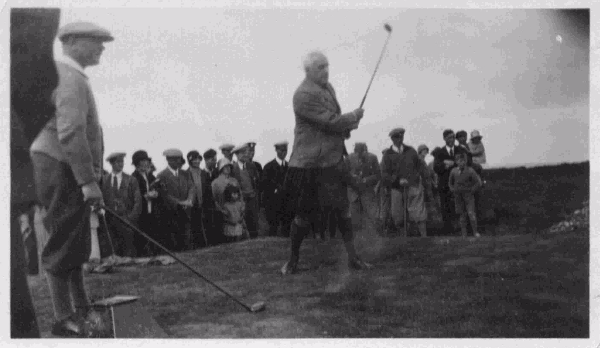

One of the most memorable dates in Findhorn’s long history must surely be Tuesday 6th July 1926 because at four o‘clock on the afternoon of that day, the tall kilted figure of Major Munro - Fergusson, brother of Lord Novar, the local laird, stepped on to the first tee, and after a brief but relevant speech to the assembled company of local dignitaries and villagers, declared the new Findhorn Golf Course open. Then, on this slightly overcast day of days with a fresh breeze coming from seaward, he teed up with a handful of sand and drove the first ball down the trim green fairway.

It is not recorded where the drive finished up and it doesn’t really matter because the spectators who had turned up to witness the opening ceremony were all in good spirit, and the historic strike was greeted with a burst of appreciative applause. Immediately after, in order to fully launch the formation of Findhorn Golf Club, the same enthusiastic crowd, having paid a shilling admission fee, followed a match between two well-known Moray professionals. Mr. George Smith, a famous club-maker of his day, and Mr Andrew Phimister of Grantown-on-Spey, the golf architect who designed the course. It was the culmination of two years hard slog and united effort by the villagers, who were rightfully proud of their tremendous achievement.

In order to appreciate exactly what had been accomplished in those days of deep depression and no government grants, it would help to sketch in a little of the background to the small community, particularly the local geography. There were three place names we children often referred to in the standard replies to their parent’s often irate question, “Where have you been till this time?” The first was “Up the road”, the second was “At the shore” and the third was “Aist the green”. The latter referred to the area east of the village where whin and broom flourished in wild profusion, broken only by occasional patches of sparse grass struggling to survive on the sandy soil. The remainder consisted mostly of tough, clumpy heather and maram grass, or as at was locally known, bent.

There was a look of unkempt wildness about the whole place, although strangely enough most of what seemed to be useless waste ground also had a practical side which was of vital economic importance to the residents. Dead dry whin was a valuable source of firewood, and bent was used to thatch the fishermen’s cottages, while the broom, which in the early summer bloomed into a glorious golden carpet, was utilised by housewives for spreading out blankets and sheets, not only to dry, but to have them impregnated with the pungent scent they would retain for weeks. In fact, where linen was stored in kists, the aroma would be discernable well into the winter months.

The terrain was mainly flattish and the most prominent feature was a large sand dune known as the Sanny Cot, and it was here that Mr Peter McAndie, the scaffie, dug holes large enough to contain the discarded rubbish of the populace. Parents naturally decreed it out of bounds, so equally naturally it was the favourite playground of their offspring.

Oh, I nearly forgot to mention that ‘aist the green’, because of it’s natural hiding places, was also the favourite courting place - at the end of every last dance in the village hall the cry went up, “ To the whins girls, to the whins”.

To carve a golf course from this uncompromising environment had, for a long time, been the dream of two men. Mr Noble, headmaster of Findhorn School and Mr John Fraser, Ranmoor. From the very beginning it must have seemed a daunting, if not, Herculean task. To organise and mastermind the clearance of hillocks, spiky bent, scrubby riggs, not to mention enough whin bushes to conceal a regiment of Grenadiers, was a massive undertaking. The aim was to convert a total wilderness into some semblance of a golf course, and in 1924 the two men surrounded themselves with an eager working party. They set about tackling the huge problems involved and, as always, money was the major requirement and so had first priority.

The original committee set up to get the ball rolling was comprised of many well-kent Findhorn names. They were as follows:

Patrons of the Club

Lord Novar, landowner, Evanton.

Mr J.F.Cumming, County Convener

Major J.M. Chadwick, Findhorn House.

Mr J Fraser, Ranmoor.

Miss McDonald, Post Office, Treasurer.

Mr S Noble, Headmaster.

Major A Ross, Hotelier, Secretary.

Miss J Storm, Findhorn, Joint Secretary.

Committee

Rev. G A McKeggie, Kinloss Parish

Mr J Robertson, Painter, Forres

Mr W Finlayson, Headmaster, Kinloss

Miss J Smith, Cullerne House.

Mr M McKenzie, Shoemaker, Findhorn

Miss J Webster, Elderslie

Mr M Anderson, Chemist, Forres

Miss J Fennie, Schoolteacher.

It will be readily understood that during the two years required to complete the work many more people were called upon to render some service of other which it is impossible to name but it will be clear from the names listed above that local affairs and community life in these days were very much under the leadership and guidance of the professional and business fraternity. In return for their keen interest and involvement if the life of the village, the villagers on whom the tradesmen depended for a living, reciprocated with a deep and genuine respect. On the odd occasions when influential muscle was required to solve some personal problem, or perhaps a domestic crisis to be handled then the dominie or the minister were the first to be approached.

The local gentry were sometimes available for background noise and display, but on the same principle as the army being only as good as its non-commissioned officers, the real headmen of the village were the professional class. Today it is a slightly different story, because with a few exceptions, most remain well in the background.

A first-hand account from the late Mrs Storm of Seaforth Place, at that time Miss Jessie Webster of Elderslie, gives an insight into the immense problems posed in raising the large sum of money needed in a society which required every penny they earned. It all began with a whist drive held in the village hall which raised £16, and then the snowball began to roll. The money was spent on materials for an army of volunteers to work with at home, wool for knitwear, cloth for needlework, ingredients to cook and bake, anything that could be converted to profit for the cause. Meantime there were others, mostly women, who cycled for miles around the countryside, especially to farms, collecting fruit, vegetables and dairy produce. Come wind or rain, shops in Forres and Elgin were canvassed for donations. In the words of Mrs Storm “it was an affa kiav,” but their efforts paid off for at the first sale-of-work held in a garage at Ranmoor during the summer over £700 was raised, a truly fantastic sum for those days. It was undoubtedly the last and finest combined fund-raising for the troops in the war years.

From then on it was all systems go; dances, concerts, more whist drives and jumble sales, all contributed to the kitty, until the great day came when all available sources were marshalled and work on the wilderness began. It must be remembered that luxury goods such as bull—dozers to uproot and flatten’ the unwanted undergrowth, nor mechanical diggers to excavate and filling did not exist. Axes, saws, scythes, hatches and shovels were the main ingredients, well supplemented by muscle-power, and an abundance of faith, hope and determination,

Two important factors favoured the organisers. The first was the soft sandy sub-soil, and the ease with which it could be worked, and the second was the availability of a keen hardworking work-force. The country was on the slide towards mass unemployment and a soul-destroying depression, and Findhorn was included in the whirlpool. The village, with only the occasional coaster using the harbour was almost entirely dependent on the salmon-fishing industry for its existence, and many fishermen during the months of the close season filled the bill admirably. Of the others many were local men of the Merchant Navy normally employed by the once great shipping companies with illustrious names such Blue Funnel, White Star and Cunard - paid off because their ships were lying idle in the strike-bound docks of the major ports. These work teams created some extraordinary contrasts, stewards from the luxury liners wielded spades alongside captains of cargo vessels, and highly skilled ships’ engineers wheeling barrow loads of earth, rubbed shoulders with deckhands, but with Mr. Nobel at the helm, Mr. Fraser as first mate and Andrew Phimister as navigator, the work progressed, as they say, a pace, and the only prolonged hold-ups were caused by adverse weather conditions, when the ground was snow covered or ice-bound. Hillocks of mussel shells, the debris of countless years of baiting hand lines for the yawls, were laboriously wheeled away by horses and carts to be spread elsewhere to provide a firm base. By the same method, sea-washed turf, gifted by Mr.R.Cunningham of Kinloss House, and reckoned by many experts to be the best in the country, was lifted from the carse and used for surfacing the greens and tees. Fertile black soil had to be fetched from various places in the Laich, spread on bare areas and planted with grass seeds to create fairways, but slowly and surely the landscaping began to predominate and the shape of the course became discernable. Excess whin bushes were uprooted or burnt away, and on what had once been stony riggs, grass grew fairways appeared, and the lush turf on the greens knitted and took root.

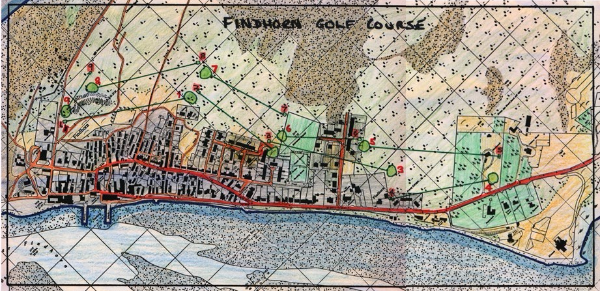

It was two years of heavy industrious effort coming to fruition, and every blade of grass growing was a triumph, until eventually the great day arrived when there emerged from the one-time wilderness Findhorn Golf Course. The high standard of workmanship throughout can best be judged by the fact there are still unmistakable signs of the greens and tees to be found nearly thirty years after its ignominious closure. The completed course was of nine holes, and was approximately 2650 yards in length, stretching roughly from the Culbin Sands Hotel to Cullerne House; four holes out and five home, it was a typical seaside holiday course, most of the hazards were natural ones, no water traps and few trees and what slight hills there were caused no hardship. All in all the whole setting was extremely pleasant, and the only difficulties for golfers were the clumps of thorny whins which had been left and the village itself, especially on the outward half.

On the right hand side of the first fairway, well within striking distance stood several thatched cottages and tangles of clotheslines. At the second was Nellie McKay’s henhouse to be considered and only yards behind the green was the tennis courts. On the third hole, Fraser the Butcher’s vegetable garden was a favourite rendezvous of the golf balls, while alongside the fourth the main road ran parallel the length of the fairway.

Luckily there was not the same volume of mobile windows as there is today. On the home run it was fairly straightforward starting with the short fifth, then a longish sixth bordered by sandy riggs before going on to the seventh, perhaps the trickiest of them all because of the plateau green surrounded by bushy broom and whin. The eighth was a drive across the Ladies Walk to the green tucked in behind the Sanny Cot, and the ninth had a very narrow fairway with a fairly high ridge which hid the green about thirty yards east of the clubhouse. This clubhouse, by the way, was made and donated by Mr Fraser, who described it at the time as a “temporary wooden clubhouse”. It still stands today, fifty-seven years later, and is used as an ablution on the caravan site.

There must still be a lot of golfers around who remember with affection the matches played against neighbouring clubs in the atmosphere of carefree style and friendly rivalry. The clubhouse was never licensed, but the Culbin Sands Hotel was only a few steps across the road. In the early days it was owned by Major Ross, a retired army officer, and later, in the middle thirties it was taken over by Mr Peter Cruickshank of Grantown-on-Spey. Luckily for the club, both were keen golfers, and both were mine hosts of the old tradition, so it was not unusual for match opponents to do the first nine holes then pop across to the hotel for some rejuvenation before tackling the second nine.

In fact, some of them just stayed there and tossed up for a result; the proximity of the bar with its internal bonhomie ruined many a good score card and by rights should be included as a course hazard.

I think a brief glimpse of Major Ross here would not go amiss for he was one of the most fascinating characters to pass through Findhorn. The Major was a huge figure of a man, known to one and all by his rank, who had come up through the ranks in the Scots Guards the hard way, and was Regimental Sergeant Major until after the 1914/18 war when he was promoted Captain-Quarter master, the only commissioned rank available to rankers in Guards regiments. For his hotel he introduced motor cruiser trips into the Moray Firth and the harbours around it in his yacht ‘Chevrons’. They would depart early in the mornings under the very capable guidance of Jimmy Storm, loaded down with hampers and crates, some of which even contained food and vanished out to sea. It was a merry bunch of holiday-makers who returned on the evening tide.

One other pet scheme of his, which unfortunately never got off the ground, was the introduction of camels into the Culbin Sands which before forestation was pure desert for the distance of twelve miles between Findhorn Bay and Nairn. He was discouraged from the idea when it was pointed out that feeding the camels would be a serious problem, otherwise by this time there would probably be pyramids across the water. As well as these inspirations and running an excellent hotel he still found time to give magic lantern shows for us children, a real treat then, and was joint secretary to the Golf Club, and responsible for the organisation at affairs and events.

Later in the summer of 1926 the club appointed their first green keeper / professional, a Forres man by the name of John Bowie. He had recently married and when he and his wife Jean arrived in the village they lived in Radio Cottage until in the early thirties they were allocated one of the two newly built council houses — the first ones ever in Findhorn. Jock proved to be a very popular choice because he was a first class green keeper and an excellent golfer. In fact his record score of twenty nine for Findhorn’s nine holes was never bettered and on top of that was a very fine teacher, With the occasional help of Peter McAndie, who kept the fairways trimmed with mowers pulled by his pony, the course was kept in good shape, and there were always progressive alterations and improvements.

At first Jock operated from a garage at Ranmoor, but was soon installed in the shop at the clubhouse. He always looked the part dressed in plus tours, diamond stockings complete with coloured garter tabs, and, of course, the bonnet. Although that was the era of the “Oxford Bags” for golfers, plus fours were the “in” thing, while the ladies stuck to the tweed skirts, with little white ankle socks and tammies for headgear. There were naturally exceptions to the rule and two young girl visitors who came to Findhorn every year, played regularly in tennis shorts. Their names, I think, were Gracie and Jean, and they must have been tremendous players because every morning there was a bevy of eager partners waiting ready to play a round with them.

About 1933 when I was about twelve years of age, I got my first job, and a coveted job it was, with Jock Bowie. It consisted of tidying up, caddying, cleaning clubs, and when Jock was busy on the course, selling tickets. It was only a seasonal number but a very busy one at the height of the summer holiday period. Findhorn was always a popular resort and the influx of regular visitors was something everyone looked forward to, as the money they brought in was essential to the economy of the place.But not only that, they certainly got things going in the village by organising dances, concert parties, golf matches, with all proceeds going to local charities. One of the star turns was Ian McKenzie who later reached professional stardom as Michael Howard with his own radio show, and appeared in several films. My pay was half-a -crown a week (about twelve and a half pence) but there were perks, which in those days of great unemployment and social deprivation, made it up to what was a respectable contribution to the family budget. For instance, the going rate for caddying was sixpence a round, there were golf balls to find and repaint for resale, but the hardest task of all, clubs to clean. Emery paper and elbow grease in equal parts were the ingredients required to remove rust, and polish up the old style irons with the nearly forgotten names of cleeks, mashies and niblicks. Nowadays the poetic names have disappeared and dull computer type numbers differentiate between clubs, but on the other hand the modern ones are made of highly polished metals that need an occasional wipe with a damp cloth. But undoubtedly the most valuable perk was learning the great game itself with all the free professional advice and coaching absorbed simply by listening to Jock instructing his paying pupils, and passing on his knowledge to more mature players. I hasten to add that all the free tuition didn’t do me as much good as it should have done.

There came a day when Jock asked me if I’d like to caddy in the afternoon. He didn’t say who it would be, only that it was someone special and would I look a bit tidier than usual, so I whitened my sand shoes, combed my hair, and bolted my dinner. It turned out to be probably the most famous person to play at the course. He was Mr Ramsay MacDonald, the Lossie loon who became Prime Minister, visiting Findhorn as a guest of Sir Louis Greig, who holidayed with his family regularly at Findhorn in the month off August. Generally speaking, the family spent their time on the water, but played golf when the tides were unsuitable.

It was a memorable day because the news of Mr MacDonald’s arrival and intentions went round the village like wildfire and when he eventually appeared in his grey knickerbottom suit there was already a small crowd assembled, and much applause when he got ready to drive off the first tee. I would like to be able to boast of some world-shattering remark or brilliant piece of witty repartee from this world famous orator, judged by some historians to be second only to Mr Lloyd George, but alas I cannot. He asked my name and said, “Well Willie, it’s your job to tee up my ball and make sure we don’t lose it”. I thought at the time he had only the one golf ball, but learned he was very short-sighted. However, all went well and I can still remember when we walked off the ninth green through a by now, large crowd of spectators. I felt like Jack Nicklaus striding down the eighteenth at St Andrews leading the field by six strokes. Such is the power of reflected glory.

There was a short sequel to this triumphant entry. When I joined my colleagues at the clubhouse there was a heated discussion going on about how much I would get paid. The normal fee was a sixpence hut all agreed that a personage of Mr MacDonald’s calibre must be rich beyond our wildest dreams, and there was much in-depth summing up such as, “Look at his big car,“ “Did you see his claes?”, “He comes from London ye ken”, and so on. Conjectures got wilder and wilder and the majority thought a fiver would be about right, and some of our fathers never mind us, had never even seen a fiver, so the suspense built up to fever pitch.Two hours later, after Mr MacDonald had burst the balloon by driving away in his limousine, Sir Louis Greig came over to the clubhouse and handed me a shilling. Apparently as the host, it was he who paid. The golf clubs I had picked out to buy were returned to the shelf, and the dream ended. Rule Britannia.

Jock Bowie stayed with the club until 1937 by which time I had left the village. With his wife and, by this time, young family, Jock took a job as golf professional at Wick and from there he was called up for war service in the RAF and when hostilities ceased, once again became a civilian. In 1948 he got the job he had always wanted, that of a pro at his home club in Muiryshade in Forres. He died tragically in 1955 but will always be remembered with great affection by the Findhorn boys of my generation for the old clubs and balls he gave us, along with much advice, and installed in our young minds a life long interest in the game of golf.

Jimmy Sutherland was the next Green keeper / professional, and the club marched on from strength to strength. New ideas kept coming forward to reshape and improve the course, lengthen a hole here, tighten up a fairway there, until September 1939, when the Great Destroyer arrived - the Second World War. Jimmy was called up and it was the beginning of the end. Local voluntary help played a great part once again in keeping the course and club together, then the members began to disappear as the Armed Forces pulled them into the ranks. Troops arrived into the area and the course became part of their training ground, trenches were dug, barbed wire entanglements appeared and thousands of pairs of ammo boots, over the next four years did irreparable damage to the once carefully nurtured links.

Like countless other British Isles communities, the life-style of the tiny Moray Firth peninsula was sadly interrupted. The armed forces whittled away local men and women of service age and led to a rapid loss of members, so the call-up of the club professional was crucial. The takeover by the Army could be described as profound military stupidity when it is considered that if the troops had been kept off the comparatively small area covered by the course, and stuck to the hundreds of useless acres only fifty yards further east, the course could have been spared much punishment without any loss of pace to the war effort.

When the war ended demobilised members and others made strenuous efforts to get things back to normal as quickly as possible, and Mr. Davie Cowper made repeated attempts on behalf of the club to get a War Damage Grant, but when eventually the authorities relented, it was too little too late. Nothing like enough to pay for the repair the ruts and bruising caused by the passage of heavy lorries and tracked vehicles, and countless other defacements. In the meantime, for reasons which remain obscure the Golf Club had decided to amalgamate with the Tennis and Bowling Club under the umbrella of Findhorn Sports Club, a move however well intended, which turned out to be a costly one for the golfing fraternity.

Of this immediate post-war period I found a general reluctance to discuss in detail the slow decline of the club, and the decrease in interest in the upkeep of the course. The prime reason for the death-knell of the Golf Club was the fact that the War Damage Grant was never spent on the reconstruction of the course, but diverted to the relaying of a new surface to the tennis courts. Who took this decision nobody knows, and there is a complete absence of documentary evidence, so we are left trying to segregate fact from fiction from the varied accounts of that strange situation. The only real fact is that the hard fought for golf course was denied the cash transfusion which was the only hope of survival. It is always easy to be wise after the event, but it is reasonable to assume that with the business acumen available in committee, plus the financially wise of the membership, there had already been deliberations on how the money could be used to the greatest advantage to the course. So what happened? If it was petty pique or local jealousy, both of which are plentiful in parish pump politics, it was a costly mistake and an expensive lesson.

A self-help scheme devised by the membership was initiated to keep the interest going until the war-time malaise passed. It was only intended to last for a limited period, but in spite of the fine example set by a few die-hards, the plan slowly petered out and finally ground to a halt. Unfortunately, no one can play golf and cut fairways and roll greens at the same time, so the self scheme proved a failure. But there was to be one more glimmer of hope. Royal Air Force Kinloss, made an offer to provide men and machines for the renovations and upkeep of the course. There was however, one major snag - in return for this generous gesture the RAF wanted priority of membership, but the locals were not prepared to concede this and the offer was rejected. Again we have to wonder if it was the correct decision. Was the offer negotiable? Could not a fair deal be worked out to the satisfaction of both parties? Apparently not, for the Air Force withdrew from the controversy leaving the question - would half a loaf not have been better than no bread at all? In the summer of 1954 it was all over.

So the course slipped away. Findhorn Golf Club, which had been formed so courageously in 1926, the course which had been created from wasteland into a successful social asset, and by 1939, the year war broke out, had settled into a lush green oasis in the sand dunes, staggered to a halt and died.

The first and ninth holes are now smothered in caravans, Nelly McKay’s henhouse, one of the many hazards, has been replaced by Linksview and Seaforth Place while the playing field cornered the second green. The third fairway and “Pop” Fraser the butcher’s garden has been straddled by Fyrish Road housing scheme, and an impenetrable screen of whims has reclaimed the whole area east of Ranmoor. The sitting room of Number I Bay View rests on the fourth tee and Heath Sands with its dark curtain of trees lies astride the fairways of the fourth and fifth hole. So too does the new by-pass road to the beach.

If you care to take a walk some fine summer evening, eastward across the green with the scented breeze from the broom filling your nostrils, and the sun slanting on the yellow gold of the bushes, if you can take your eyes off this magnificent splash of colour thrown against a blue sky for a few minutes and look downwards you will find here and there patches of turf greener and richer than they should be in texture.

That, my friends, is what is left of the once proud Findhorn Golf Course.

Bill Shand